long long-termism

thinking four generations ahead

Most of the great accomplishments in human history would be considered failures by modern standards.

They took too long.

They paid off too late.

They demanded faith from people who would often not live to see the end result.

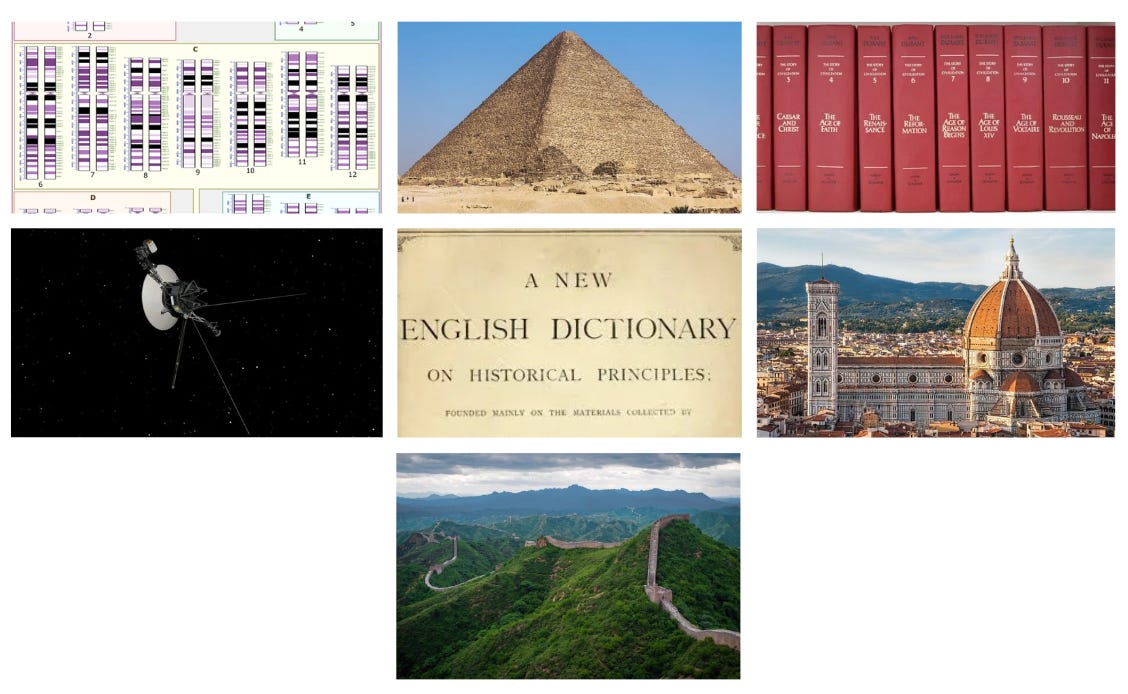

The human genome? Completed in 13 years.

The Great Pyramid of Giza? Constructed in 26 years.

The Story of Civilization? 11 volumes written over 40 years.

NASA’s Voyager mission? Active in space for almost 50 years.

The first Oxford English Dictionary edition? Took more than 70 years.

Florence Cathedral? Its famous brick dome was completed over 140 years.

The Great Wall of China? Construction lasted 9 dynasties across 2,300 years.

These feats of human ingenuity did more than inspire generations.

They defined entire centuries. They changed the way we looked at the world.

These were not accidents of genius, wealth, or technology.

They were bets on the future, placed by individuals who understood something we have now largely forgotten: great things take time.

Short-termism is a losing strategy

Modern life is optimized against anything that requires time.

We have been conditioned to strive for immediacy.

News is breaking 24/7. Metrics refresh constantly. Content updates automatically. Scrolling is infinite. Code is vibed in minutes. Writing is prompted in seconds. Rewards arrive instantly, or not at all: if something does not pay off immediately, it feels broken.

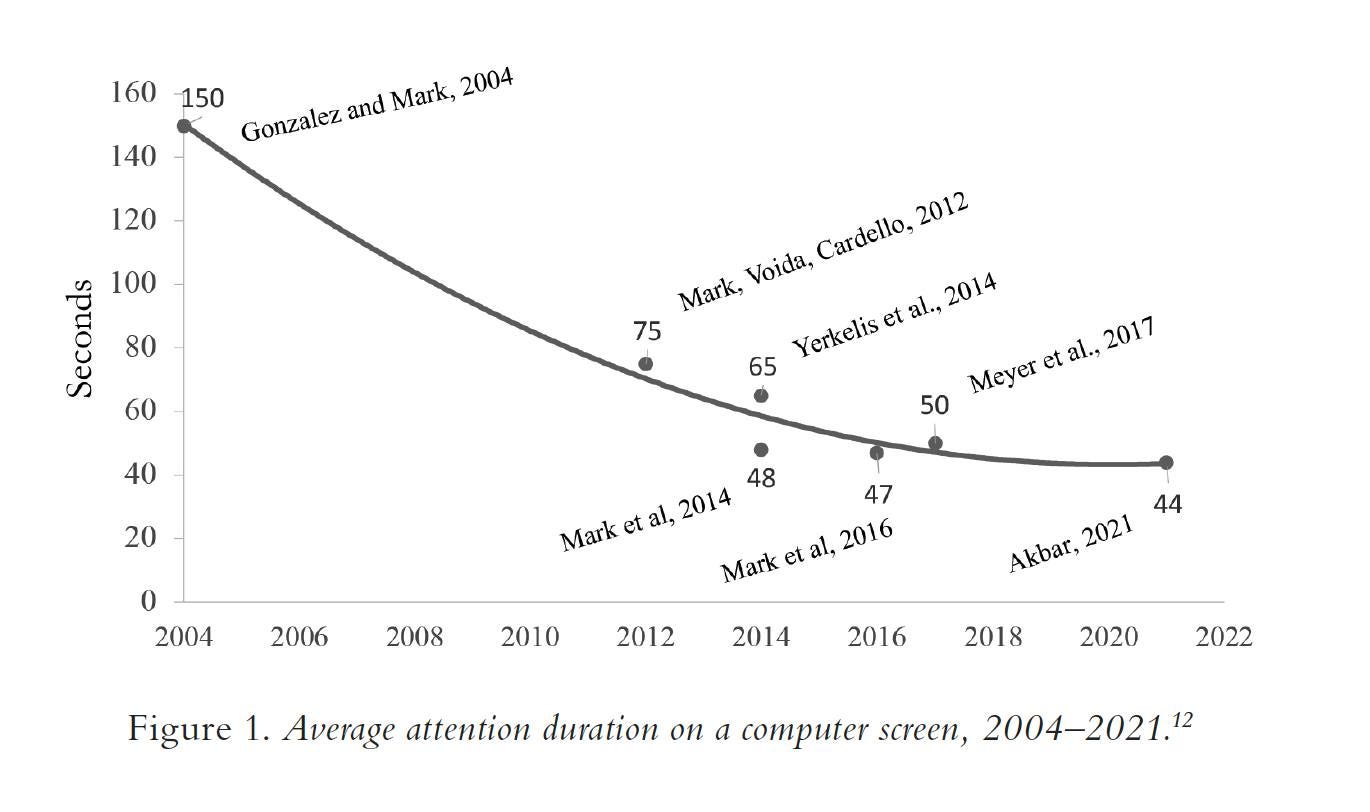

Our attention span has become narrow. We have become too impatient. Difficulty is no longer tolerated.

We expect quick results and instant gratification, often leaving things unfinished or skipping half-way through just to get to the next shiny toy.

The moment something gets hard, we swipe left.

This logic governs more than our relationships with our phones. It shapes how we learn, how we work, how we build companies, how we treat relationships, how we grow friendships, and even how we enact policy.

With the prevalence of digital screens everywhere and a dopamine infested culture in everything that we do, we struggle to focus on any one thing more than a few seconds. We skim instead of studying. We sample instead of committing. We abandon before compounding has a chance to even begin.

There is a deep problem with this way of living.

Both our bodies and minds have taken notice.

The cost is subtle but cumulative.

Anxiety rises. Autoimmune diseases multiply. Satisfaction declines. Inspiration becomes rare. Not because we are incapable of depth, but because depth requires effort, and taking our time with things has become a heresy.

This is a losing strategy for humanity.

Going long on the long-term

Our future is built right here, in the present.

Layer by layer, decision by decision.

Every single choice counts.

Building new things is not enough. We need to make them durable too. Lasting. Resilient. We need ideas that age well, institutions that resist decay, systems that do not collapse under the weight of their own success.

Most plans today are evaluated on quarterly, annual, or at best 5-year (classic business plan) long timeframes.

But the consequences (intended or unintended) of our most important decisions do not respect such temporal boundaries. They often unfold across many generations.

Our best chance to maximize positive change and minimize catastrophic mistakes is to think, plan, act and invent beyond our own lifetime.

Global life expectancy at birth today is 73 years. That’s about ~3 generations long.

Thanks to innovations in medicine and healthier lifestyles, many people now live well into their 80s and 90s. That’s getting closer to witnessing ~4 different generations within our lifetime.

So, here’s my proposal: Let’s make 100 years — a total of 4 generations — the minimum planning unit for the most important decisions affecting our societies.

Not because we can predict the future. On the contrary, because we choose not to mortgage it on behalf of our descendants.

What if we intentionally bet (i.e. go “long”) in the people, ideas and creations that actually make the best case for humanity’s long term success?

I call this mode of thinking (going) long (on) long-termism.

Looking 100 years ahead

Long long-termism is optimistic about the future.

It means stretching responsibility over many generations and owning our share of it.

It entails the willingness to start epic human undertakings whose rewards would not arrive for decades, or even centuries.

And it is the conviction that the power of our sustained efforts over time has a compounding effect that can result in exponential results.

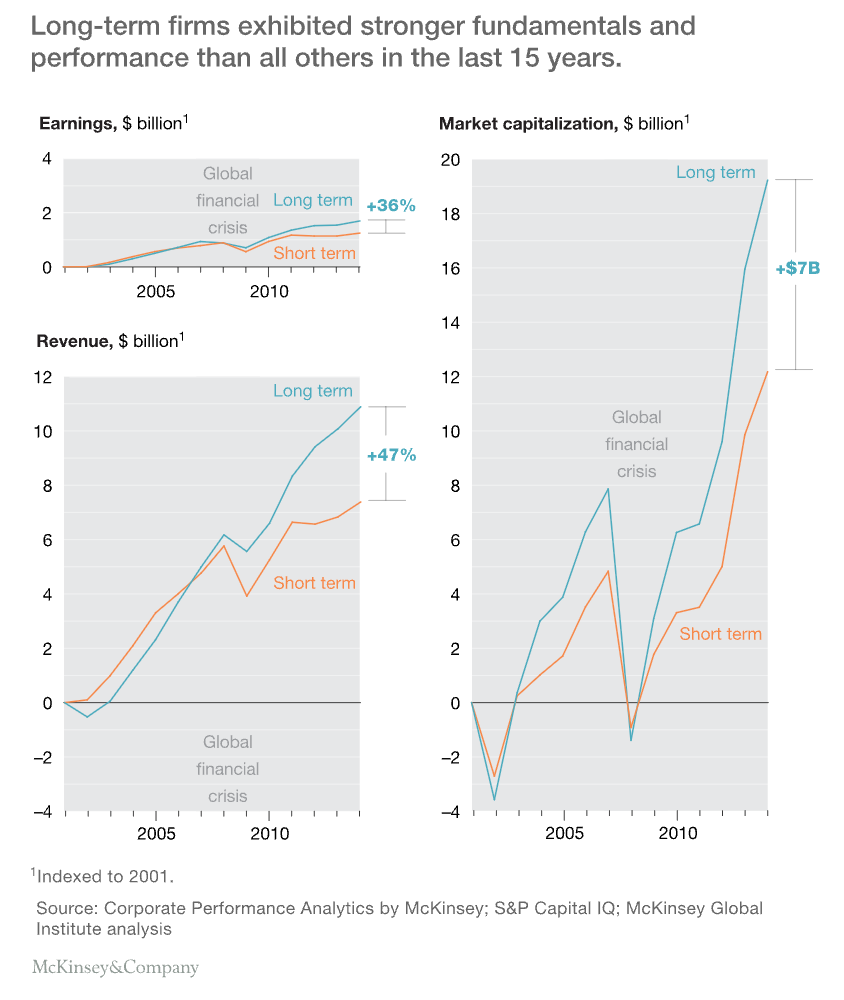

This is not just a moral stance. It is also to our economic best interest.

Going long on long-termism pays off.

Organizations that adopt long-term strategies consistently outperform those trapped in short-term cycles. The evidence is clear.

As children, our favorite fairytales often started with the phrase “a long long time ago”.

As adults, we should make sure our ideas include the phrase “a long long time ahead”.

Long long-termism means rooting for progress, supporting civilization-building activities and investing (time, money, influence, resources) in initiatives that improve our collective future.

Long long-termism prioritizes compounding over speed, resilience over optimization, and stewardship over extraction.

Long long-termism is the most human point of view one can take about life: acting in ways that take into consideration our children, our children’s children, and even our children’s children’s children, therefore increasing the chances of biological survival for our species.

Models of long-term thinking

Long-term thinking sounds abstract. In practice, it is a discipline we can quickly observe if we pay attention around us.

We can find it in institutions that lasted centuries, in creators who worked for futures they would never see, in investors who chose hard (but lasting) wealth generation over easy (but ephemeral) breaks of fortune.

These are not ideals to romanticize, but models to learn from. Let’s look at a few.

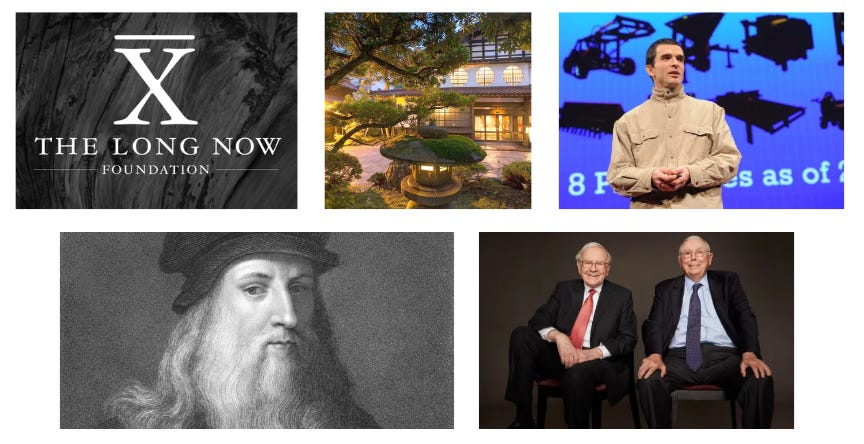

What would it look like to think more like The Long Now Foundation?

As the most future-oriented institution in the world, Long Now aims to “creatively foster responsibility” and make us think about the next 10,000 years. Going against the tide of “faster, cheaper, larger”, it has been promoting an alternative way of “slower, better, more durable”.

What would it look like to operate more like the Hōshi Ryokan?

Hōshi is a ryokan (Japanese traditional inn) founded in 718 AD. It has been owned and managed by the Hōshi family for 1300+ years over forty-six (yes, 46) generations. It holds the record for the oldest, continuously-running family business in the world.

What would it look like to design more like Leonardo Da Vinci?

Da Vinci lived many years into the future, leaving behind a wealth of extraordinary inventions, engineering designs and artistic creations that are still universally admired and used 500 years later.

What would it look like to invest more like Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger?

The most successful investing duo of all times surpassed everyone else by consistently investing in great companies that exhibit durability, resilience and long-term potential. They held these companies in their portfolio for decades, often never intending to part ways with them.

What would it look like to plan more like Marcin Jakubowski?

Marcin is the founder of Open Source Ecology, a global collaborative project whose mission is to develop a modular set of 50 machines and tools that can be used to (re-)build everything we need for human civilization from scratch (assuming things, well, go kaboom).

These are not the expected, desired or even possible outcomes for every one of us. But they do present examples that we could learn from when thinking about some of our most consequential decisions.

Not a map, but a compass

Long long-termism does not give us a complete map of the future.

That would be arrogant. Dangerous. And boring.

Instead, it offers a simple standard to live by. A compass for uncertain times. And what is that compass directing us towards?

It tells us to take our time with ideas that are worth exploring. Trust the process of compounding and benefit from its exponential power. Act in ways that still make sense when we are too old or even long gone. Build things that will outlive us and do not need us to survive. Take decisions our great-grandchildren will not end up cursing.

Ultimately, leave this world meaningfully better than we found it.